- Home

- Julia Dixon Evans

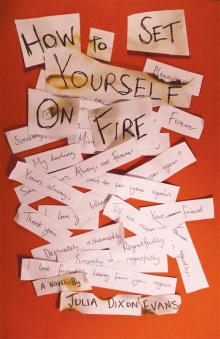

How to Set Yourself on Fire

How to Set Yourself on Fire Read online

HOW TO SET

YOURSELF

ON FIRE

HOW TO SET

YOURSELF

ON FIRE

A NOVEL

JULIA DIXON EVANS

5220 Dexter Ann Arbor Rd.

Ann Arbor, MI 48103

www.dzancbooks.org

HOW TO SET YOURSELF ON FIRE. Copyright © 2018, text by Julia Dixon Evans. All rights reserved, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Dzanc Books, 5220 Dexter Ann Arbor Rd., Ann Arbor, MI 48103.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Evans, Julia Dixon, author.

Title: How to set yourself on fire / Julia Dixon Evans.

Description: First edition. | Ann Arbor, MI : Dzanc Books, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036657 | ISBN 9781945814501 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Granddaughters--Fiction. | Family secrets--Fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3605.V3657 H69 2018 | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036657

First US edition: May 2018

Interior design by Leslie Vedder

Cover by Matt Revert

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

“In the end we had pieces of the puzzle, but no matter how we put them together, gaps remained, oddly shaped emptinesses mapped by what surrounded them, like countries we couldn’t name.”

—Jeffrey Eugenides, The Virgin Suicides

ONE

IT’S THE THIRD MORNING of a wildfire to the east and everyone’s used to the smell by now. Still, I’ve been awake for hours and my brain seems to crawl inside my skull, equal parts anxious at and tired of the smoke. Every wildfire season, when a thick blanket of ash hovers between the fire and the ocean, I wonder if I’m far enough from it, if this concrete grid of hundred-year-old suburb will repel fire the same way it repels me. Maybe fire will feel right at home here, the same way I do. Every wildfire, I feel safe and I don’t feel safe. I care and I don’t and this is my California. From the concrete walk of the courtyard, I count the ants in twos as they rush across the tops of my shoes, two, four, six, dozens, hundreds, too many to possibly all know where they’re going. There’s nothing out here for them, just sidewalk cracks, lifeless plants leaning against the walls, cheap patio furniture, my neighbor’s ashtray, the low-hanging loneliness heavy in the air. I wonder what the ants know that I don’t.

Greyish-orange skies yield to heat already and I hear my neighbor start up a Skype call. It’s barely six.

“Hello, Vinnie,” a woman says. His ex. She lives on the East Coast somewhere with their daughter, Torrey. I know all this because his place is so close to mine. I’ve listened to Torrey grow up on the other side of these video calls. I’d feel more like the creeper I am if Vinnie weren’t so obnoxious and unconcerned with being loud at 6 a.m. I’d feel more like the creeper I am if I knew how fathers were supposed to be with their daughters.

“Sarah,” Vinnie says. Clipped. “Where’s Torrey?”

“She’ll be down in a minute. We have to discuss next summer, though.”

“For the love of God, it’s November.”

He says this the same way he says What’s happening when we meet at the mailbox. The thing with Vinnie is, he doesn’t get louder. He never shouts. He has one volume.

“These things take serious juggling, and if you’re not willing to step up and plan—”

“Oh, don’t give me that.”

“I’m just saying. All her friends are going to summer camp here. Maybe this isn’t the right year for her to come to you.”

“Sarah, I’m going to pretend you didn’t say that.”

I can hear him moving around in his apartment across the tiny courtyard that links our two miniscule buildings. He must be in the kitchen because I don’t see movement through the single window. I shake off my shoes but the ants just reassemble. Some guy from the building behind our courtyard shouts, like he always does, “How about you shut the fuck up, Daddy?” but Vinnie ignores him, like he always does.

I try to remember the last time I slept.

“Hey, Dad,” Torrey says on the other end. “I scored a goal this weekend!”

“Oh yeah?” Vinnie says, and I feel a weird fondness for his sudden shift in tone. “That’s so great.”

I tune out. I realize that it’s unfathomable to me to be on either end of that kind of conversation. Of that kind of relationship. I am not a father. I am not a daughter. I am not my father’s daughter.

I brush the ants off with my hands and go inside. I almost slam the door, but I find myself not wanting to make a bad impression on a girl on the other side of the country. My phone rings, but it takes me a minute to place the noise. The last time I heard that ringtone was when I picked it from the settings.

It’s my mother. Run, I think, like there’s another fire on the other side of the phone.

I let it ring. After a minute, she calls again.

“Hi, Mom,” I say.

“Sheila,” she says. “It’s Mom.”

I lean against the cabinet in my kitchen, really just a corner of the single room I live in.

“Hi, Mom,” I say again.

“When’s the last time you visited your grandma?” she asks, the your placing guilt squarely on my shoulders.

“Uh, last week?” I say. It was probably a month ago.

“Well,” she says, and she takes a deep breath. I can tell she feels important and serious. She lives for this shit. And I understand the 6 a.m. call. “I think you should visit her as soon as possible.”

Hang up, I try not to say out loud. Run run run.

TWO

MY GRANDMOTHER IS VERY old, and tonight, she’ll die in her sleep. But right now, she says, “I have something to tell you, sweet girl.”

She’s wrinkled—shriveled really—but she still looks like me and my mother. We each inherited her wiry blond hair and bony knees and shoulders. My grandmother’s hair is grey now, neck-length. She looks away, her chin down, and she doesn’t look happy but she also doesn’t look afraid, and that’s how I’ve always known her. Her papery hands clutch a small shoebox to her stomach. She holds it tight, like it’s hardwired into her blood. I try to keep my eyes off the box. It’s a child’s shoebox, and I know without question that the shoebox is sixty years old and once housed something of my mother’s. I don’t know what shoes my mother wore as a kid. The shiny Mary Janes she forced on me when I was very small? Lace-ups? Miniature penny loafers? I doubt my mother was the type to scuff the toes or wear down the soles into rubbery shreds, like me.

“History always repeats itself,” my grandmother tells me. Or maybe she says, “History never forgets,” or maybe that’s just what she’d always say at Christmas, at the dining table, her forearms resting on the red poppy-covered tablecloth, whenever people were arguing about something pointless. We’d all laugh because we wanted her to be funny. Nothing is funny now.

I smile at her. I’m something between vaguely uncomfortable and curious and I shove my hands beneath my thighs so I have something to do besides grab the shoebox. I want to egg her on.

“Yeah?” I ask. She’s never been much of a talker and neither have I. It’s not uncommon for us to sit here in silence for the entirety of a visit. I both love this and feel like I’m failing her.

She closes her eyes and nods her head, once, twice, and then leans it back against the stack of pillows propping her up. I can already tell I’m not going to get much more out of her.

The room oppresses me. It

’s too big for just a twin bed and two wicker chairs. I don’t think about my grandmother, the way she has always been there for me: loving, but a few steps away, and I don’t know if that distance was me or her. I focus on very recent history, my second appointment with a therapist in many years. I think about the prescription tucked into my wallet, which I’ll never get filled. This room is too big for my tiny grandmother, tiny not really in size but in the way she doesn’t take up space. When I was younger, she’d be sitting with us at our house, right in front of me, and still sometimes I would wonder where she’d gone. In an assisted-living facility, an old woman shrinks more than ever. She looks like she’s somewhere else, like she’s never belonged here in the first place.

“Okay, Grandma,” I say. “What do you mean?”

Then she asks me to leave. She says, “Go now, sweet girl. Not today. I’m tired. I’ll tell you tomorrow.”

It’s quiet in the courtyard outside my house. The sun is about to come up, the chilly air full of marine layer and morphing from black to grey to golden-grey. I haven’t slept much at all tonight. I shiver, sitting on my front step, but I had to get out of the sweltering heat of my house. My neighbor’s ashtray perches atop his green plastic patio table. I could probably reach it if I stretched—pick up the discarded cigarette stubs and see what was left of them. When I hear movement inside his place a minute later, I stand up, silent, and slip back inside without thinking. Without thinking why I don’t want anybody to see me. Without thinking why I don’t want to see anybody.

I dial Jesse’s number, the number of a man I knew so well but who never knew me at all. When I was a teenager, doing this sort of thing with boys, I’d have to stop before I got to the last number so the call didn’t go through. But it’s a touchscreen now, and I can dial all the numbers, see them stretched out like a sentence. I like the way the numbers look all in a row. Sometimes I type the numbers a dozen times over and it’s beautiful, a plea: You’ll never know how good we could be.

I have his number typed all the way out when my phone vibrates and the screen switches over to an incoming call. My mother.

“Sheila?”

“Hi, Mom,” I say.

“It’s Mom,” she says. And then, “She’s gone.” Just like that.

“Oh,” I say. Just like that. It’s not as breathless as I hoped.

“Did you see her yesterday?” she asks.

“No,” I lie. I wonder why I lie.

When I get to the nursing home, my grandmother’s body is gone and the room is packed in tidy boxes. I open them all, carefully at first, tucking everything back in place and trying to restick the tape, but before long I get impatient. I tug box lids until the corners bend, and things don’t fit back in after I ratch through each box. I want the shoebox.

When my mother arrives, I’m sitting on one large box and rummaging through another, and she makes a face—pulling her chin back toward her neck and scrunching her eyebrows. If I tried that, I’d look foolish, but she manages to look graceful. She seems startled to see me, but I cut her off before she can ask me something like: What are you doing going through all of your freshly-dead grandmother’s boxes like this? And then: Have some decency, she’d add.

“Hi,” I say. “Just checking all these.” I don’t really want to give her time to respond. “Did Grandma leave out a little shoebox?”

She glances to the side before she answers. “What shoebox?”

Two weeks ago, I started getting nosebleeds. At first I panicked. I read websites about how to treat nosebleeds and combed through the hashtags. There’s always pictures. Not of the nosebleeds but of their happy lives, despite a bloggable medical issue. Their children are well-adjusted. Their houses are nicer than mine. They are better at photography. They are better at social media. They are better at living with nosebleeds.

“Less stress, more salt,” my doctor suggested. A pause, then: “Have you ever thought about psychiatric treatment?” I laughed and he said, “I didn’t mean it like that,” with his hand on the doorknob, and I wondered if they taught him to act like a bad boyfriend in medical school or if he was born with it.

By now, I’ve stopped panicking. I stop trying to treat the nosebleeds. I like the way the blood feels as it leaks from my nasal cavity into the back of my mouth. I like the way the blood looks as it drops onto Jesse’s letter. There’s just the one letter. It’s not even addressed to me.

A tiny drop falls onto Jesse’s salutation. My dearest love is now blotted with my cells and plasma and it’s almost like he loved me too.

When my mother is at work, I let myself into her house. It’s unusual for me to be here alone, but I am here enough otherwise. She’s lived in this place my entire life, opting, for private reasons, not to leave as her family dwindled from three to just us two, to finally one. I never go upstairs anymore. A small part of me wants to see my old room, to sneak up there, and an even smaller part imagines her coming home while I’m upstairs. I imagine her face as she notices me in here, holding her accusations on her tongue, her withered nostalgia, her I wish we were still close and Whatever happened to the two of us and Look, it’s just us, just like the olden days. Do you want some tea? Some Prosecco? And I imagine her face as I walk past her, down the stairs, and leave without telling her why I was in the house, without giving her any answers to the questions she would never have the balls to ask me. But today I have other plans.

It’s not hard to find the child’s shoebox because it’s sitting on the countertop beneath a small stack of paperwork from the nursing home and the mortuary. I stuff the box in my purse. It fits, but one corner of the lid tears and I feel I’ve disrespected my grandmother and my mother, not because I’m snooping but because the shoebox lived so long without being damaged, until me.

I don’t leave a note.

The shoebox sits untouched on my coffee table. Frontline is on PBS, and I’m masturbating.

The lone window in this tiny house is closed and the volume is up, but across the small courtyard, I can still hear Vinnie Skyping with his kid and his disgruntled ex-wife. I hesitate every time I hear the twelve-year-old girl, because it sends me down a mental rabbit hole.

Vinnie is insufferable when he’s talking to his ex-wife, but I sort of like him when he talks to his daughter. She’s quiet, often bored, sometimes absurd. I think she thrives on saying the things her parents are expecting her to say the least. Vinnie is sweet with her, patient in a way he and the ex are not with each other.

Last summer, when Torrey was out here for two weeks visiting her dad, I stayed inside as much as possible but could hear every word they’d say to each other.

“You can’t just write Pop-Tarts, Dad,” Torrey had said.

“Listen, this is the most detailed grocery list I’ve ever made. The only time I’ve ever used capital letters.” I could hear the smile in Vinnie’s voice. I was on the couch in my tiny place, lying with my head flat on the seat and my feet up on the armrest, a portable fan pointed directly at me.

My father, when he shopped, never used grocery lists. He’d meander the aisles, navigating by feel. Half the time he forgot the ingredients for dinner. But he’d always buy the treat foods—the Pop-Tarts. The things with capital letters.

“You gotta write strawberry Pop-Tarts,” Torrey said. “It’s important.”

“Whatever you say, champ,” Vinnie said. “Strawberry it is. All the other flavors are terrible.”

“Well,” Torrey said. “Let’s not get carried away.”

Vinnie just laughed. He just seemed genuinely happy to be making a finicky grocery list. Charming. Vinnie was and is charming with Torrey. And I’m consistently impressed with his ability to chin up and not only call his ex but look at her on a video call. I’m impressed, and then quickly sad. My father couldn’t even muster up a phone call. And then, past the sad, I’m pissed. Stop. I grasp a breast in one hand, squeezing, lifting.

“Look, I’m not going through this again!” Vinnie shouts.

“Vincent, don’t do this in front of Torrey,” Sarah the Ex says.

Frontline is a rerun, which is fine because nostalgia is all I have room for. They’re doing a montage of evening news program sound bytes about Obama’s first term. My hips shift. I press harder.

I close my eyes. They’re showing a clip of a White House press conference. I’m so fucking close I can feel it low in my gut, spreading.

“I’m not doing anything,” Vinnie says. “Let Torrey choose how she wants to spend her own goddamned summer!”

Nancy Pelosi says, “I call it the dance of the seven veils. I’m going to be there, and then I’m not, and I’m going to be there, then I’m not, now you see it, now you don’t,” and she sounds insane.

“Stop it!” Torrey finally says, angry, and it’s the first time in a long time I’ve heard her at a pitch above apathy. “I don’t want to go to any dumb summer camps.”

I’m angry, too, as I come, because it’s not even any good.

THREE

WHEN I FINALLY OPEN the shoebox, PBS is still on, but it’s the weird late-night stuff. Vinnie is sitting in the shared courtyard, smoking and playing phone Tetris with the sound on. I breathe deeply, his expunged smoke satisfying the nicotine addiction I never properly kicked. I consider Vinnie’s hygiene, the way he dresses, the way he doesn’t seem to take care of himself, the way his hands look so worn, so used. I breathe deep again.

My fingertips twitch to hold something, to fidget with a cigarette. I rub the edges of the shoebox lid, its cardboard softened with age, more cloth than paper, and I think about my grandmother’s skin, how it didn’t look soft. She looked hardened, wooden, etched. I lift the lid.

It’s letters. The shoebox is full of letters, more than I can even begin to estimate. Small ones, the personal envelope size that nobody uses anymore. Only one of them has a stamp and a postmark. The stamp is unfamiliar. The postmark is faded but still clear: SAN DIEGO. MAY 13TH, 1950.

How to Set Yourself on Fire

How to Set Yourself on Fire